META-INSTITUTES

We might imagine that the French Revolution failed because it installed itself in the buildings of the royalty it overthrew. While proclaiming a new social order, replete with new system of measure (the rational Metric system), a new metric calendar (ten months to a year), a radical declaration of universal human rights new to Europe, and other innovative ideas, the Revolution chose as its architectural setting the royal palaces of the ancien regime. While promising a new world order, it delivered an old world order of space and symbol. It was, perhaps, an understandable mistake—adopting the trappings of familiar power to borrow its authority—but it was fatal. Symbolically, the Revolution offered itself as merely a substitute for the old order, just another form of elite, begging to be rebelled against and overthrown. What, we might ask, would have happened if the Revolution had immediately proposed a new order of civic space, one reflecting its rational ideals—new town plans, a new plan for Paris (think of Le Corbusier’s Ville Radieuse), and new types of public buildings, including those for the governing elite of the nouvelle regime itself? We will never know.

We might also imagine that the Russian Revolution learned a lesson from history and inaugurated itself with the most radical designs imaginable for buildings and towns, at least in its earliest phase. Constructivist design, which included a revolution in print graphics, clothing, theater, film and music, as well as architecture and urban planning, was based on the premise that changing the social order meant changing the aesthetic order, indeed that the ethical and the aesthetic were not only synonymous but synchronous—you cannot invoke one without invoking the other. Perhaps, we might speculate, the new Socialist order failed because this understanding was abandoned after a decade or so, when the new order assumed the borrowed authority of the old royal, Tsarist trappings in the form of a Stalinist dictatorship that housed itself in the imperial Kremlin and commissioned neo-classical ‘skyscrapers.’ What would have happened, we cannot help but ask, if the social revolution had been realized in the visionary Constructivist designs? In other words, what would have happened if the political revolution had proved to be more than words? Might we now be living in a brave, new Socialist world? Perhaps not, but we will never know, for sure.

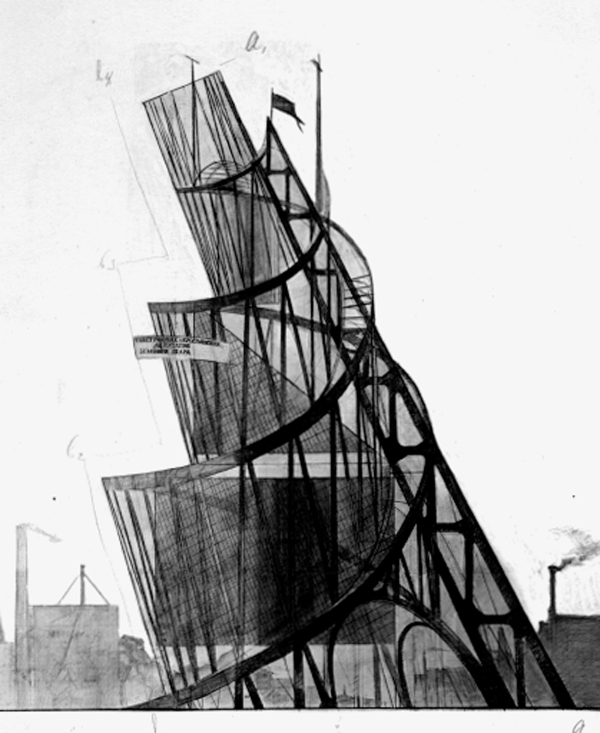

It is difficult to imagine carrying on government-as-usual in Vladimir Tatlin’s spiraling ‘monument to the Third International,’ with its suspended, rotating chambers, which was intended to house a radically new Socialist form of government. At the same time, it is easy enough to picture a labyrinthine bureaucratic regime carrying on quite as bureaucracies always have in the Kremlin, or in Albert Speer’s pseudo-Greek buildings designed for the Nazi Reich. Phony revolutions are a perfect fit for phony architecture, or for architecture that inauthentically borrows its authority from a pre-revolutionary past. It is fortunate that the United States is not undergoing a political or social revolution, given its pseudo-Roman Capitol and neo-classical White House, though Barack Obama did campaign on a promise of “change” that culminated on a stage festooned with phony classical columns.

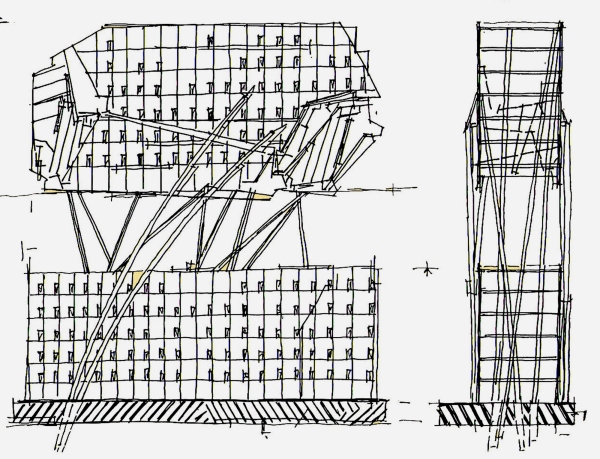

Tatlin’s Tower was actually a new building type, one with little history and even less foreseeable future, which I have called a “meta-institute.’ Simply put, it is a building designed to house an institution for the study of the very idea of institution. When a new form of government must be created, a study of government must, in itself, be the first order of business. A building that breaks out of the familiar models or types can become an experimental tool in the process, at the very least an example of new thinking and a stimulus to innovation. The very spaces where discussions and debates about the new form of government are offered and carried on should be as much a challenge to old ways of thinking as new laws and principles, thereby linking the intellectual to physical reality. In effect, a meta-institute should present a spatial problem to be solved that reflects the ideological one: solving one aids in solving the other.

Kazimir Malevich (center) and others at the First All-Russian Conference of Teachers and Students of Art, Moscow, 1920:

PETROGRAD, Russia. Vladimir Tatlin, Monument to the Third International, 1917:

Bastardized version in a Moscow street demonstration, 1927:

Tatlin’s “tower” as seen in the skyline of Petrograd:

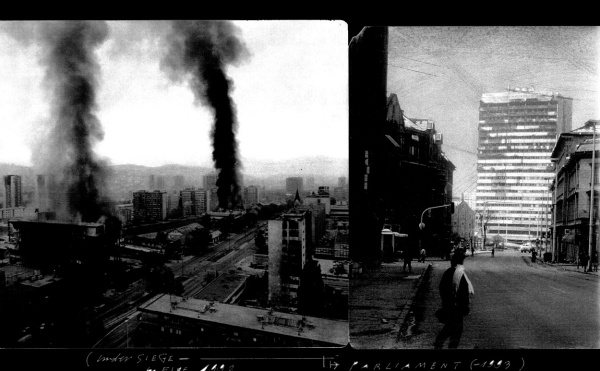

SARAJEVO, Bosnia and Herzegovina. The city under siege, 1993; the damaged Parliament building on the right:

Haris Pasovic, Ivan Straus, LW (all center) and others at the “War and Architecture” exhibition in the damaged Olympic Museum, Sarajevo, 1993:

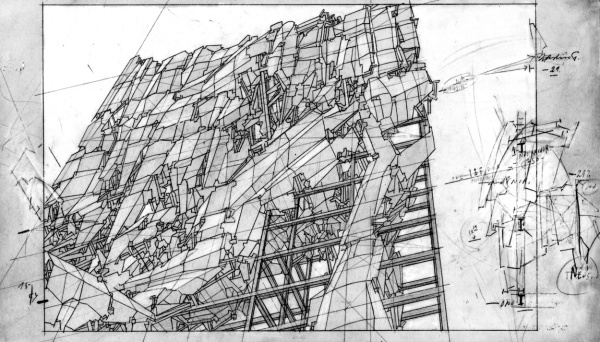

LW proposal for the reconstruction of the Parliament Building:

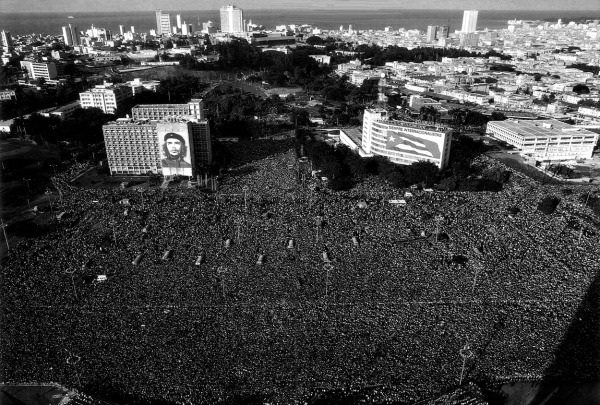

HAVANA, Cuba. Government organized political rally in the Plaza of the Revolution, late 1980s (photo by Gianfranco Gorgoni):

Mojitos at the La Bodeguita del Medio:

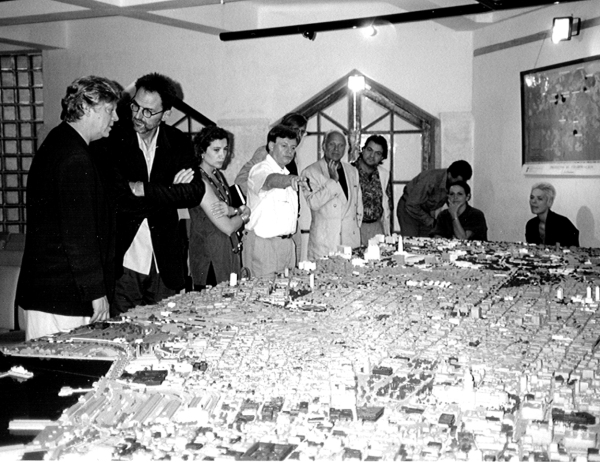

Meeting at the “Architecture Again” conference, 1994, l. to r., LW, Thom Mayne, Carme Pinos, Mario Coyula, Wolf D. Prix, Carl Pruscha, Gianfranco Gorgoni, unidentified, unidentified, Daniela Zyman:

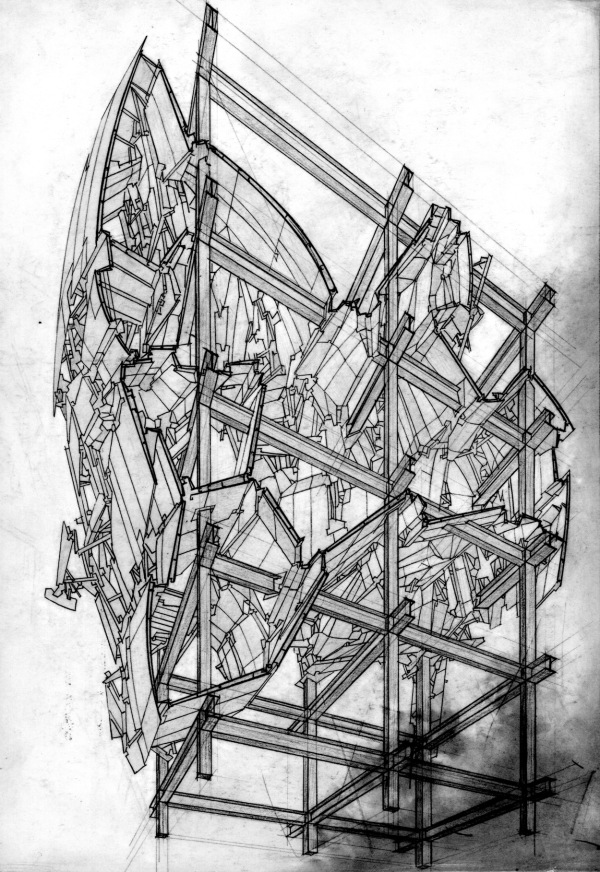

LW proposal for a Meta-institute:

Meta-institute seen from the Old Plaza:

LW

About this entry

You’re currently reading “META-INSTITUTES,” an entry on LEBBEUS WOODS

- Published:

- August 1, 2009 / 3:31 pm

- Category:

- Lebbeus Woods

- Tags:

6 Comments

Jump to comment form | comment rss [?] | trackback uri [?]