ORIGINS

(above) Site of the Arnold Engineering Development Center (AEDC) near Tullahoma, Tennessee, c. 1950, showing the Elk River Dam and Woods Reservoir, named in memory of Colonel Lebbeus B. Woods—my father—officer in command of its construction (portrait photo inset on the right).

.

I am the son of a distinguished Air Force officer and bear his name. He died in 1953, at the age of fifty-two, from a rare form of blood cancer caused by his involvement with the development and testing of the atomic bomb, though his service record blandly states his cause of death simply as “a result of service.”

He was born to parents who were school teachers in the wilds of South Dakota, on a large Sioux reservation. After joining the U.S. Army in 1918, he took the highly competitive exams to enter West Point and with only his equivalent of an eighth-grade education, got in. Graduating as an officer in 1925, he resigned his commission to become a civil engineer for the Pennsylvania Railroad, designing and directing the construction of railway bridges until the outbreak of the Second World War, in 1942.

He continued his engineering work in the Army, building airfields, bridges, and other necessary facilities in England and Europe as the Allies steadily advanced against the Axis forces. In 1944 he was assigned to the Manhattan Project in Los Alamos, New Mexico, to construct the buildings and other structures needed by Robert Oppenheimer, Edward Teller, and other scientists there, to develop the atomic bomb. His first exposure to radiation was the bomb’s test at the Trinity site; his second, in 1948, was at the Bikini Atoll in the Pacific. Five years later, he died a painful death—as had hundreds of thousands of others, both Americans and Japanese.

In that brief period, he accomplished a final mission: the building of the Arnold Engineering Development Center (AEDC), a sprawling experimental facility in southern Tennessee, that, since its completion in 1953, has been vital to the invention and development of air- and spacecraft and their jet or rocket propulsion systems not only for the military but also for NASA projects such as the Space Shuttle. A large manmade lake, made to supply enormous quantities of water needed by the Center, but also famous for its ecologically protected woodlands and wildlife, is named in his memory.

I was born into and spent my early years during a time of war, first a hot one and then ‘cold,’ but my childhood experiences unfolded—oddly enough—in a milieu of creative engineering, problem-solving, and construction. Patriotism was a given so there was no ideological contention at home. My parents were both FDR Democrats—he was also as good as given—so there was little political debate, either. What was important was getting the job done for good reasons. Up to age thirteen, I spent my free time reading, drawing, hanging out around jet aircraft and their pilots. I and a few other officer’s chldren used to sneak down to the flight-line, watching jet fighters and bombers take off and land, then have cokes in the flight-line café where their pilots went for coffee, still dressed in their flight gear. Once, at the air-base in Ohio that was my father’s last command, I climbed some fences and wandered for hours in a vast field of derelict fighters and bombers, exploring them inside and out, until MPs showed up and took me into custody. It seems that some of these planes had been used in the Bikini atomic tests, and it took hours of medical exams, interrogation, and my father’s high rank, before I was returned home to the officers’ quarter of the base.

I also grew up around a certain kind of architecture, though I’m certain I didn’t call it that or have much of an idea of what the term meant. I suppose that I would now call it functional architecture, because its uses dominated the genesis of its form; still, it had a self-conscious aesthetic and a design intent that included its visual qualities and the emotions they evoked. The building forms and their meanings are in a way romantic and fantastical—wind tunnels, transonic circuits, gas dynamics laboratories—-a kind of architecture for opening up and exploring new worlds. Even the more conventional industrial forms of steam plants and other support buildings reflect traces of the glow of a great adventure, experienced in this context of immensely consequential invention. All of it stayed with me, though was not to emerge—radically transformed—until many years later.

LW

General Carroll, Colonel Woods (second from the right) and their group inspecting the landscape of the AEDC.

.

Colonel Woods with building contractors on one of the construction sites. A telling bit of trivia: In those days, a military officer’s everyday uniform was clean, well pressed, and plain, and not so different from the everyday business clothes of civilians. Today, the everyday uniforms of officers anywhere are crumpled camouflaged combat fatigues, worn as though they were ready to go into combat at any moment.

.

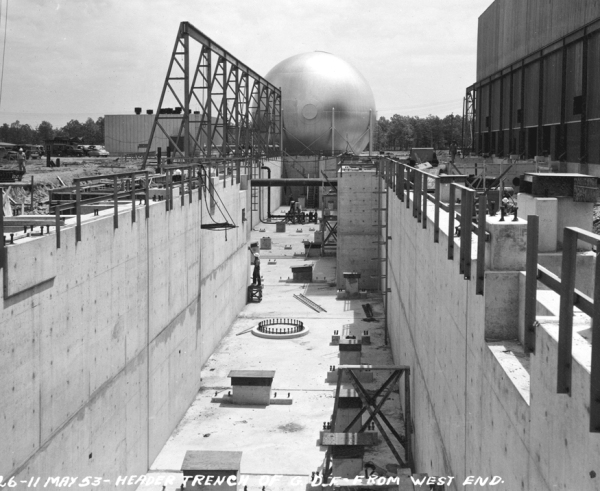

The Transonic Circuit—a wind tunnel for testing air- and spacecraft in dense atmospheres at extremely high speeds.

.

The Gas Dynamics Facility is most heavily involved with developing jet and rocket propulsion systems.

.

.

A newly developed jet engine being tested.

.

One of several shops devoted to making scale models of air- and spacecraft prototypes and components for testing.

.

Related posts:

https://lebbeuswoods.wordpress.com/2008/11/13/big-bang/

https://lebbeuswoods.wordpress.com/2010/09/14/terrible-beauty-3-i-am-become-death/

About this entry

You’re currently reading “ORIGINS,” an entry on LEBBEUS WOODS

- Published:

- January 2, 2012 / 9:51 pm

- Category:

- Lebbeus Woods

10 Comments

Jump to comment form | comment rss [?] | trackback uri [?]