FELLINI’S DREAMWORK

Sigmund Freud considered dreams “the royal road to the unconscious,” a glimpse into a world of mind we inhabit without knowing it, except when we dream. Even then, we do not know it as we do the world we are conscious of, because this world—the unconscious—is revealed to our conscious minds only in fragments that often seem irrational and incoherent. Freud, however, believed they made a great deal of sense, if only they could be ‘translated’ in terms of our conscious experiences. Not only that, but understanding the sense they made was vital to our mental health.

This is hardly the place to explain Freud’s theories or argue for or against their validity. A great many books doing just that have been written in the hundred or so years since the publication of The Interpretation of Dreams, a founding text for the field of psychoanalysis. It must do for now to know that over this past century Freud’s theories have been applied with success to aid in the treatment of various forms of mental illness—including everyday stress, anxiety, and depression brought on by the demands of modern living. Of equal importance, perhaps, is that these theories have entered our culture in ways that enlighten our understanding of what it means to be human, influencing both our critical and creative capacities in art and science.

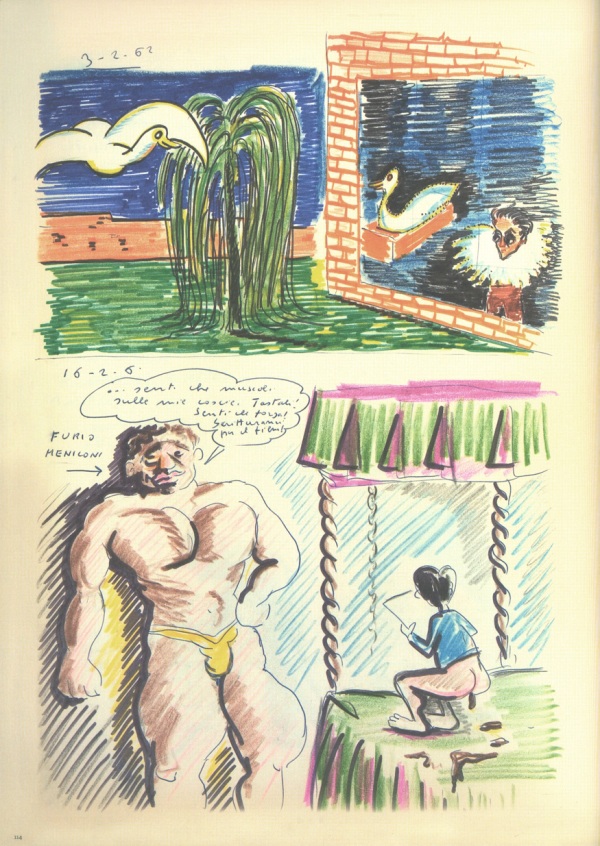

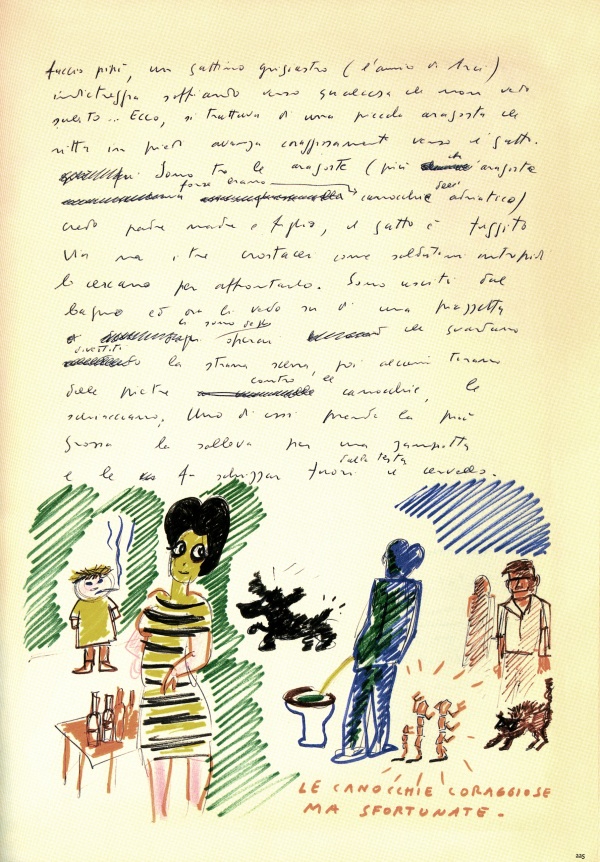

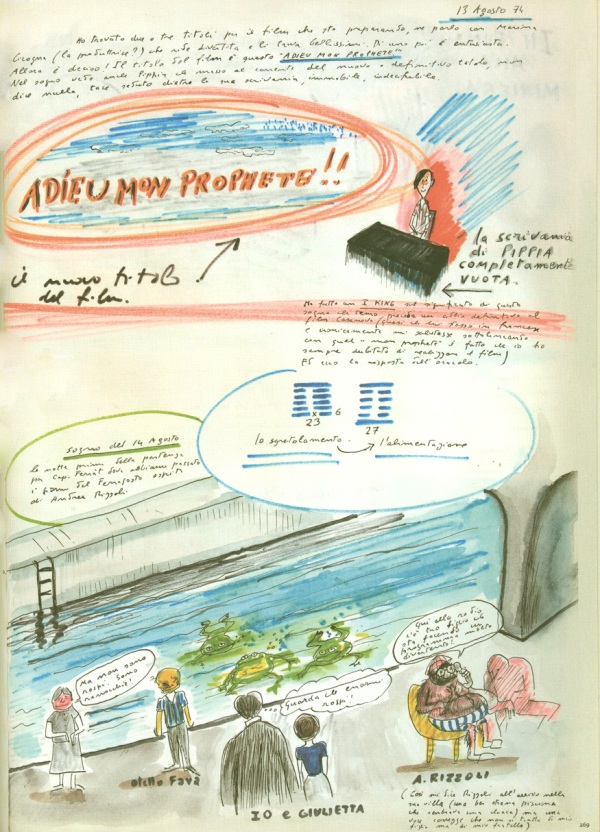

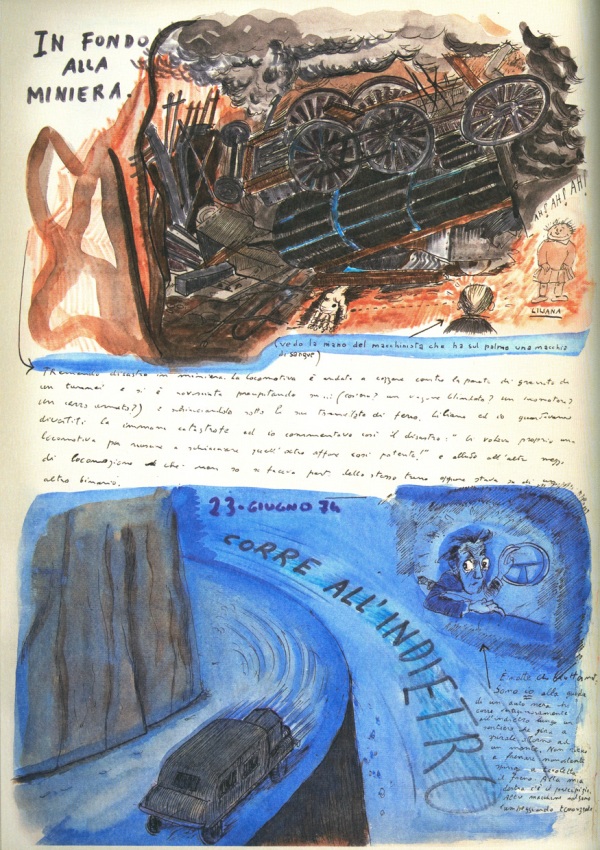

I feel fairly certain that Federico Fellini, one of greatest film-makers in the history of cinema, which just happens to span the same century as psychoanalysis, knew all about its theories and even spent time on the psychoanalytic couch. Regardless of whether he did or not, he did spend a great amount of his time recording his dreams, in exactly the way Freud would have appreciated: noting every detail he could remember in words and drawings. The good Doctor would have had a field day with them!

If you can read Italian, there are Fellini’s notes in the samples below from a recent publication entitled Federico Fellini: The Book of Dreams. If, like me, you cannot, you can refer to English translations in the book’s appendix, or, have your own field day with appreciating the drawings, both for their startling originality and freedom of technique, and as points of departure for making your own psycho-analysis of Fellini and his films. For example: what part of the human anatomy does he seem most obsessed with? And why? That, as they say, is only the beginning.

LW

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

About this entry

You’re currently reading “FELLINI’S DREAMWORK,” an entry on LEBBEUS WOODS

- Published:

- December 19, 2011 / 8:07 pm

- Category:

- Lebbeus Woods

- Tags:

- drawing, dreams, Federico Fellini, psychoanalysis

18 Comments

Jump to comment form | comment rss [?] | trackback uri [?]