VISIONARY ARCHITECTURE

“They’ll tear down your building in twenty-five years. All that will remain are its ideas.”

Louis Sullivan

“….but what if it never gets built?”

anonymous

The term ‘visionary’ generally refers to a person (and things he or she does) who exists somehow apart from the real world—as in ‘having visions’—and it is usually reserved for saints and the brilliant-but-unbalanced. It is a term used to marginalize certain architects and their works, and in that sense, is both pejorative and highly political. Still, it is almost instantly understood by most as having to do with the innovative and the new and on that limited basis serves present purposes.

The two examples of visionary architecture posted here each exhibit at least three essential attributes.

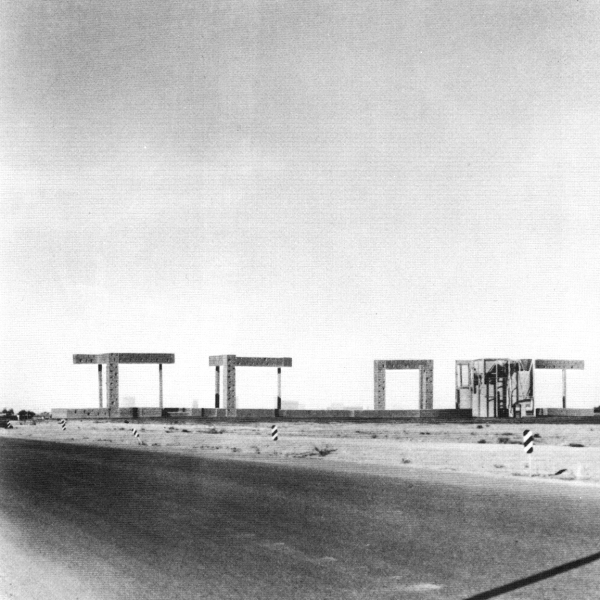

First: the projects propose new principles by which to design for the urban conditions they address. In the case of Steven Holl’s 1991 project for Phoenix, Arizona, he gives the city a distinct edge, rather than allowing it to continue sprawling helter-skelter into the desert. His argues for the establishment of the city’s physical identity, and for the desert’s—each is to be spatially defined, though porously, so that they are not cut off from one another. In Le Corbusier’s 1924 Plan Voisin for Paris, the historically overburdened center is to be replaced with a rational matrix of widely-spaced modern buildings heavily interspersed with lush parks and gardens. Both offer radical new conceptions of these cities and their transformations.

Second: the designs are total in scope. All scales—from the individual dwelling unit to the overall urban field are addressed and integrated. Also considered are the physical relationships proposed between architecture and nature, the sky and the ground, as well as the conceptual relationships between the past and the present, the individual and the society, and other such weighty philosophical issues. A vision sees the world whole.

Third: the designs invent new types of buildings. Existing typologies are not useful to implement the new urban principles. Holl’s “retaining bar” buildings and Le Corbusier’s “cruciform” skyscrapers were new building types, creating new relationships between people, and between people and the landscape they inhabit.

Is or was it ever likely that either Holl’s or Le Corbusier’s visionary projects would be realized? No. Did that matter to the architects? Not likely. So, why did they make them? To unequivocally articulate a set of architectural principles and design ideas —and to test them. Were the drawings and models made by the architects sufficient to accomplish these goals? Yes. In both cases, the drawings and models were made to be clear and understandable, to any intelligent person, but especially to critically minded architects.

There is an instructive story about Plato, who was an architect only in the sense that he envisioned the ideal social architecture of a human society—The Republic—in his Dialogues. Upon hearing about it, a certain Dionysos, the tyrant of Syracuse, was so enamored of Plato’s ideas that he invited him to come to his city and establish the ideal society in reality. Plato, for reasons that are not recorded, decided to accept the tyrant’s offer, so off he sailed. After only a month, the intrigues of Dionysos and his court—who felt threatened by the radical new ideas—became so intense that Plato had to flee, and was lucky to escape with his life.

Did Plato fail to ‘realize’ his vision of The Republic? Yes. Did that prevent the ideas of The Republic from having further influence? Hardly—they have been some of the most influential political ideas in history. Indeed, their not being realized has undoubtedly helped keep them alive for so long.

LW

Steven Holl’s “Edge of a City” project for Phoenix, Arizona (c.1991):

Le Corbusier’s “Plan Voisin” for the center of Paris, France (c.1924):

About this entry

You’re currently reading “VISIONARY ARCHITECTURE,” an entry on LEBBEUS WOODS

- Published:

- December 11, 2008 / 9:13 pm

- Category:

- Lebbeus Woods

- Tags:

12 Comments

Jump to comment form | comment rss [?] | trackback uri [?]